Are Kiwis ready to buy breakfast online?

Mathew Parackal, Rory Redman, Damien Mather and Peter Cox

Online shopping is gaining popularity with customers, particularly for grocery products (Nielsen 2017). The convenience factor alone seems to attract people from all walks of life to online shopping, and that include high-income earners (Morganosky & Cude 2000; Ramus & Nielsen 2005; Ahmad, Omar & Ramayah 2010; Vijayasarathy 2004; Roberts, Xu, & Mettos 2003), people with disabilities and temporal constraints (Morganosky & Cude 2000). Supermarkets have been quick to open online shops to offer customers the convenience of shopping whenever and from wherever they like (Morganosky & Cude 2000; Marimon et al. 2010; Rafiq & Fulford (2005). The Tesco formats that include home delivery (Roberts Xu & Mettos 2003) and click & collect (Mercier, Welch & Crétenot 2014) are the popular ones. Another format emerge is the ‘click and drive’ (Lapoule 2014).

While the direct access to the market may be tempting FMCG brands to set up online shops, not many have made that brave move as yet. The lack of assortment, consequently the cost of shipping small quantities to remote locations is a challenge for FMCG brands. Perhaps one way to circumvent the problem is to shift focus from the product to offering customers specialised service to meet their specific needs (Dickey & Lewis, 2009). For example, a service that supplies breakfast cereal for families with Celiac disease. The automation of logistics provides an opportunity to innovate the delivery of FMCG brands as a service in the form of a plan (De Kervenoael et al. 2006). Such a plan entitles the subscribers to a variety of product (e.g. ready to eat breakfast cereals) for an extended period (e.g. month). By providing for an extended period, the quantity ordered would be sufficient to achieve the required economies of scale for delivery the product to remote locations. This paper reports a study that investigated customers’ interest to subscribe to such a plan for purchasing an FMCG brand.

Methodology

The study was carried out using Harraways Oats’ single sachets. The investigation compared the formats that customers prefer when purchasing online. Using an experimental design, three possible forms of the offering (supermarket, online product and online subscription) were studied. A market testing methodology implemented the experiment on women aged 25-35 on Facebook in Auckland and Wellington. By using postal codes, the treatments were kept separate within the two regions.

The treatments, prepared as Facebook posts, announced the Harraways Oats’ single sachets in the respective formats. The supermarket treatment, acting as the control, presented the offering as sold at the local retail stores. The online product treatment announced the availability of the offerings online and the online subscription treatment announced the supply of the product in a box for a chosen period. The posts explained the formats and posed three questions (see in the Posts) to direct the users’ line of thinking when commenting. An incentive to win a Harraways Oats hamper was offered to encourage users to comment. The posts, disseminated as newsfeeds using Facebook Advertising in the three regions of Auckland and Wellington separate by postal codes, ran for 40 days. The study generated 85 comments, accounting for over 2500 terms that were analysed using natural language processing technique. The comments were analysed separately for the treatments (control treatment =33; Online product = 17; Online subscription = 35), using SAS Enterprise Miner version 14.2 to understand the participants’ reaction to the respective offerings. By using an unsupervised machine learning technique the comments were grouped into topics, and the pattern interpreted to infer customers’ responses to the offerings.

Results and Discussion

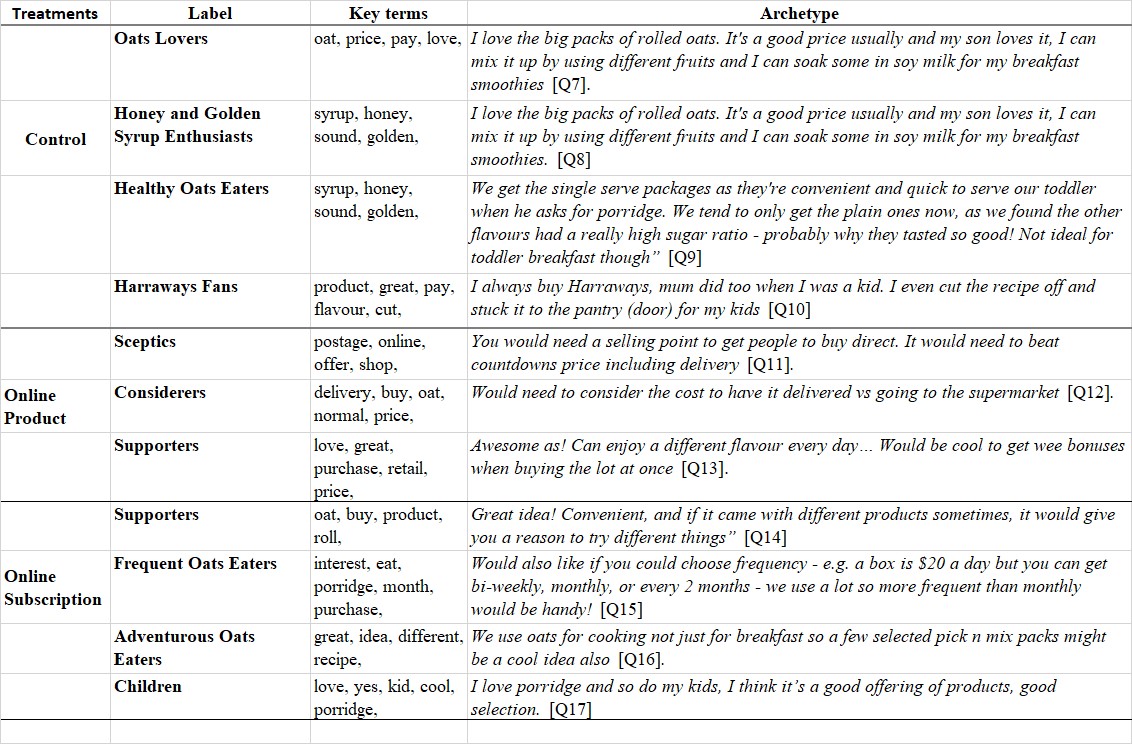

By reviewing the comments and key terms of the topics extracted, appropriate labels were assigned. Table 1 shows the labels, key terms and archetypes that define the topics for the treatments. The topics reflected the different segments of customers within the target market.

The four topics in the control treatment resonated with the traits of this brand, highlighting its popularity (see the Archetypes in Table 1). The Online product offering had support (Supporters), but there were also concerns raised for the value it provides (see the Archetypes for Sceptics) and the cost of delivery (see the Archetype for Considerers). There were three themes for the online subscriptions that included Supporters, Frequent Oats Eaters, Adventurous Oats Eaters and Children). All four topics were supportive of this offering, which is reflected by all the archetypes. It appears that all the segments within the target market favoured the subscription format.

Conclusion

This study, based on the comments, showed reasonable support for the online subscription format for this brand. The favourable response could be because of the loyalty the brand has, reflected in the comments in the control treatments. As this was a one-off study, further triangulation of the finding is needed to be done to be conclusive. While undertaking survey research could be an option to generate more market information, for the same cost, an e-commerce portal could be set up and introduce the subscription offering using the same test marketing methodology (Shih & Jin 2011). Such an investigation can generate analytics to provide a clear direction for this brand’s online agenda (Sharma & Dadhich 2014).

References

Ahmad, N., Omar, A., & Ramayah, T. (2010). Consumer lifestyles and online shopping continuance intention. Business strategy series, 11(4), 227-243.

de Kervenoael, R., Soopramanien, D., Elms, J., & Hallsworth, A. (2006), Exploring value through integrated service solutions: The case of e-grocery shopping. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 16(2), 185-202.

Dickey, I. J., & Lewis, E. F. (2009). Furthering the Integration of Online Marketing in the Grocery industry through business model and value assessment. In the proceedings of the ASBBS Annual Conference, Las Vegas, 1-8.

Morganosky, M. A., & Cude, B. J. (2000). Consumer response to online grocery shopping. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 28(1), 17-26.

Nielsen (2017), What’s in-store for online grocery shopping: Omni-channel strategies to reach crossover shoppers. Insights: FMCG and Retail. Available from: https://www.nielsen.com/nz/en/insights/reports/2018/the-rise-and-rise-again-of-private-label.html

Ramus, K., & Nielsen, N. (2005). Online grocery retailing: What do consumers think? Internet Research, 15(3), 335-352.

Roberts, M., Xu, X. M. & Mettos, N. (2003). Internet shopping: The supermarket model and customer perceptions”, Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations, 1(2), 32-43.

Sharma, N., & Dadhich, M. (2014). Predictive business analytics: The way ahead. Journal of Commerce & Management Thought, 5(4), 652-658.

Shih, H., & Jin, B. (2011). Driving goal-directed and experiential online shopping,” Journal of Organisational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 21(2), 136-157.

Vijayasarathy, L. R. (2004). Predicting consumer intentions to use on-line shopping: the case for an augmented technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 41(6), 747-762.