Values: The building blocks of our community

Dr Mathew Parackal and Dr Damien Mather

By analysing the responses to two simple questions, (What are three issues that matter to you? What are three things that make you happy?) we accurately predicted the result of the 2014 New Zealand General Election. Some might say that is ridiculous – how could the responses to two generic questions reveal voter’s political leanings? The two questions captured the values most relevant to New Zealanders. We used the values to frame their support for the political parties.

We believe our method (or system) is an improvement on the current polling systems, which often generate much of the chatter in the election cycle. Traditional polls, the likes of which you hear in the news offer a snapshot in time of how people would vote if the election were held at that moment. The problem we have with that is that the issues of the day can sway people. Arguably, the questions asked can run the risk of skewing respondents’ answers – for example, consider a poll that included a question that asked, “What do you think of National leader Simon Bridges’ limo expenses?”. The negative press around that issue could load negative sentiment, so the next question, “Who would you vote for if the election was held today?” could see skewed answers being put forward. Whereas come election day, people in the polling booth are far more likely to give the tick to the party that best connects to their values.

For the 2014 General Election here in New Zealand, we tested our method and came away very pleased with the accuracy of our results. Six weeks out from Election Day we predicted the outcome of each political party and in most cases were one or two percentage points off perfect. Keep in mind that was six weeks out, before much of the mudslinging and pumped-up promises were on the table for the public to view. Values are the key to how we did it.

We gather our sample from the 3Di consumer panel. We needed approximately 1000 people to take part. Then we ask them those two questions – what three issues matter to you, and what three things make you happy? People can write as much or as little as they like. Some wrote screeds of text, others mere bullet-points. The next step is where our method meets technology. The responses to the two questions were subjected to natural language processing techniques that identified the values relevant to the participants, and an overall picture of importance by rank ordering them.

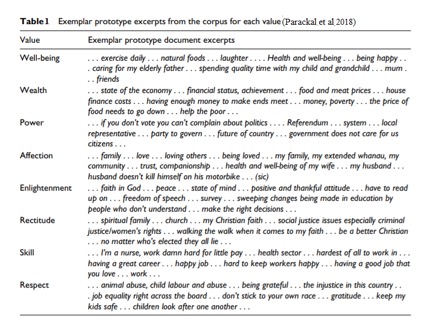

The values defined are from pioneering political thinkers Harold Laswell and Abraham Kaplan, two of the most influential social scientists of the twentieth century who wrote Power and Society, a Framework for Political Inquiry, first published in 1950. The eight values are shown in the table below from our paper published in the International Journal of Marketing Research

The values were regressed to the voting choice indicated by respondents. Based on the coefficient we can say whether a particular value will encourage voters to vote for a specific party or deflect to another. For example, if a person’s language showed that “Respect” was the value that best suited them, we knew that for the 2014 election they would be highly unlikely to vote National, and far more likely to vote Labour/Green. Another example would be if a person’s language showed that “Rectitude” at a level of 1 out of 2, we knew that they would be over 4 times more likely to vote for Labour, Greens or NZ First.

This information could potentially be highly valuable to a political party, for if they see they are failing to exhibit behaviour and policies that connect to a particular set of values, their campaign managers could potentially encourage change by communicating favourably on the exemplars from the response. For example in the case of “Respect”, parties need to focus on “animal abuse” or “child labour and abuse” (see Table 1).

Another observation from the 2014 election was the curious case of the Internet Mana Party, or as we like to describe the two parties as “iron and clay”. Our method revealed the two parties that formed the Internet Mana Party were ideologically different. We predicted the pitiful result that Internet Mana came away with on Election Day almost perfectly.

We suspect this may also be the case for the Maori Party in the 2017 General Election, following the years of support given to the National Party. Both the Maori Party and the Mana Movement failed to return to parliament. We believe a comeback for these parties would require a revival at the grass-root level and new leadership.

If our system lives up to our assurances, we believe it can enhance the election cycle by focussing political journalism and discussion more on the real issues of values, rather than sensational trivial matters that can too often draw considerable attention.

The big test will come in 2020 when Kiwis go back to the polls. Before then we’d like our system to be picked, prodded and scrutinised so we can show it stands the test of peer review and reverse engineering. We are confident it will.

One thing that is becoming clear is the changing demography of New Zealand – the people who make up the continually evolving group known as “New Zealanders”. As we become multi-cultural, the traditional left-right political partisan affiliations are getting blurred. With more choice of parties, an MMP system, and a shift from voters merely following the prescribed lead of their parents or workplace, the days of the left-right political divide is long gone, at least for the voting public. Accurate polling data provided by our values-based system could help bring the real issues to the foreground and see politicians reacting to the matters that truly matter during election campaigns. Watch this space come 2020.